The Value of Landscape Photography in the Age of AI

- Mike Page

- Jul 21

- 9 min read

Does AI Pose a Threat to (Professional) Landscape Photography?

I may or may not have mentioned that I'm currently enrolled in an online MA Photography program with the AUB (10/10, would heartily recommend). This is an essay that I recently submitted as part of my course work (which explains the slightly more formal style than usual) that bears posting here as well. Let me know your thoughts below.

Introduction

I think it must have been about five years ago as I was toying with the idea of slowly bridging the gap to becoming a full-time - or at least semi-professional - landscape photographer and I watched a YouTube video talking about the fact that it was nearly impossible to make a living merely from selling landscape photos. I forget whose channel it was, but it sounds like something that Adam Karnacz of First Man Photography* would have said.

Five years down the line, is it time to ditch the ‘nearly’ from this dire warning? Is there any value left to landscape photography in the age of artificial intelligence?

*In other news, after 6 years of following him, I finally understood the choice of brand name - duh💡.

Value

We need to start by defining what we mean by value in the context of landscape photography.

On the one hand, the value of a given work of art is linked to its uniqueness as well as its desirability (Berger: Ways of Seeing). The monetary value of a photograph is also linked to factors such as provenance, authorship and scarcity. The photograph “Rhein II” by the German photographer Andreas Gursky is reported to have sold to an anonymous collector for approximately $4.4M in 2011, but that is an exception rather than a rule. Award-winning photographers such as the Lake District-based gallery owner Stuart McGlennon typically commands around £200 for an approximately 100x50 cm (non-limited edition) print. So much for monetary value. What else might the term imply?

In a recent blogpost, the American photographer Joshua Cripps discussed printing images and looked at those adorning the walls of his private collection. He concluded that “the prints that I most love to stand in front of, as well as the prints that generate the most conversations here in the gallery, they all have something in common:… …it’s not that they are my prettiest photos, my “best” photos, or even my most popular photos, it’s that they all create a strong emotional connection with the viewer”, a sentiment that I strongly share when I look at the images that I’ve decided to hang in my own home. The ones that I value most are those associated with the fondest memories of being outside in nature, at one with the elements and my camera in capturing the moment.

Value, then, can be measured both in terms of money and emotional connection, though there may be a third aspect to the term in the context of landscape photography that I will touch on below. How might AI affect value in this context?

AI

In his essay “ChatGPT, or the Eschatology of Machines”, Hui touches on the inexorability of technological progress through the ages. The AI revolution is probably no different from the revolutions that have gone before and now that Pandora’s proverbial box has been opened, it will be nigh on impossible to reverse the process. But what is AI, or more specifically, how does AI generate images?

Currently, the two main methods of generating images using AI are Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Diffusion Models, both of which rely on vast databases of images to generate new content. Although the engines seem to be remarkably good at creating plausible images with clearly identifiable subjects, there’s still a very plastic feel to AI images, as evidenced by my recent foray into the discipline. Even dystopian images feel cartoonish rather than menacing.

But what is true of the state-of-the-art today needn't be true tomorrow. Without the immediate physical constraint of hardware and its associated time-consuming manufacturing processes, progress in the digital field is orders of magnitude faster than say the automotive industry or even of biology. The limits of today’s AI with regard to the emotional feel of the images could conceivably be overcome within a few years, if not a few months, if this is a quality subjectable to automation, which may not be the case: Charlie Engman believes that “AI’s limited understanding of bodies stems from perceiving them through images, not lived experiences.” This echoes Hui’s observation that ““[r]eflective thinking” is usually associated with human beings and not with machines, because machines only execute instructions without reflecting on the instructions themselves”.

This would suggest that the creative process is not limited by the technology involved, but by the fact that machines lack something fundamentally unique to the human condition and experience that cannot be reduced to an algorithm, however complicated said algorithm may be.

In a recent post on his Facebook page, the New Zealand-born landscape photographer Dean Nixon lists 10 reasons why photographers should not use or make AI-generated images, including the erosion of technical skills, the undermining of society’s trust in the medium of photography, the ethical issues of authorship and the devaluation of real-world experience (Nixon: Tuesday Tip #293).

The response from the photographic community was predictably vociferous: “AI is dishonest”, “It will replace me as an artist”, “It’s not ART!”. But this was also the rally of the artists’ community at the dawn of the photographic era or that of the analogue photographers’ community at the dawn of the digital age. Progress seems to be inevitable and Canute taught us the futility of standing in progress’ way.

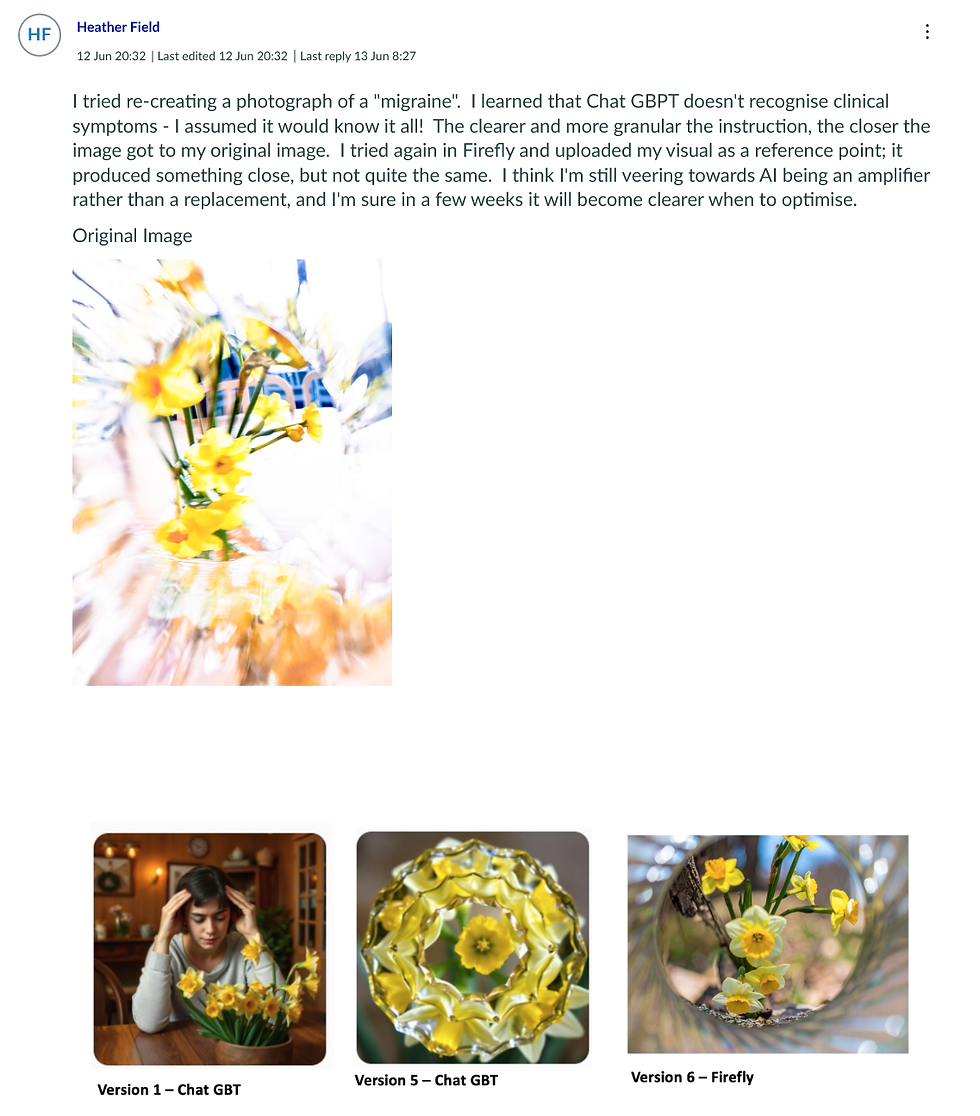

In her experiments with AI, one of my fellow students attempted to recreate her photo ‘Migraine’ using a variety of engines with varying results that all feel somewhat sanitised compared to the crunchy, emotionally-laden original. Even experienced AI-users report very variable results when using the technology to generate images. The photographer Laurie Simmons explained in an interview with Charlotte Kent for Aperture “Some days I feel like an AI whisperer, other days like a flop.”

At present, then, I would argue that AI has the emotional intelligence of a small child who has been tasked by their mother to bring out the best napkins. The infant is eager to please but unable to parse and ham-fistedly grabs the brightest, shiniest ones. Whether AI will mature emotionally remains to be seen. I suspect that Engman’s insightful observation will mean that it cannot.

AI and Landscape Photography

So how does this impact landscape photography? The landscape photographer’s adage “local sells” strongly implies that there is more to the value of a photograph than the mere image itself. What sells is the emotional connection between the buyer and the image. I saw this first hand at a photo exhibition at work a couple of years ago. Before the vernissage had even started, I was approached by colleagues who wanted to purchase three of the images I was displaying. What linked all three purchases was that in each case, the colleague in question had an emotional connection to the place in the image, whether a photograph of one of the lakes close to Munich or of the Seiser Alm in the Dolomites where he had spent formative time as a child.

Can AI create images with a similar emotional connection? I’ve tried to recreate an image by the American photographer Mark Denny that I came across recently, taken overlooking the famous Seceda ridgeline in the first snow of autumn by using OpenArt and DALL-E with far from satisfactory results:

To be fair to AI, Adobe’s Firefly (which, like DALL-E, also employs a diffusion-model-based approach) did a much better job of understanding the task (not shown), but it still lacks the impact of the professional’s image. Would I buy a print of Denny’s photo? If I didn’t have any myself, almost certainly (though mine aren’t quite as stunning as his). Of DALL-E’s? I have no emotional connection to that place, if it actually exists outside of a computer’s imagination, so the answer is a clear no!

Landscape photography cannot be restricted to the image itself. It’s always about the story. In the end, the image is just a by-product of a long process. That process involves scouting locations (either in person or in silico), planning, developing the skills to be able to capture the image in the field, the excursion itself, execution and capture followed by post-processing. Perhaps my favourite piece of photographic equipment is my worn pair of hiking boots. It certainly isn’t my keyboard.

In her book “Landscape Matters”, Liz Wells sums it up as follows: “Artists collect, log and sift through a diversity of information about places in order to deepen the insights that will inform photographic method and processes. They are not journalists going in and getting the shot; rather they are storytellers whose depth of research and analysis is reflected in the philosophic perceptions and visual rhetorical strategies which characterise their picture-making.”

The product of many popular YouTube photographers isn’t the image per se, it’s the adventure, the story from conception to acquisition. As Ian Gillan once sang with Deep Purple, “it’s not the kill, it’s the thrill of the chase”.

As my fellow students and I were discussing our photographic niches in POD704: Professional Practice, James Elliot was quick to point out that one aspect of the product that I’m selling as a photographer is the experience of obtaining images of the mountains in exciting settings. It’s all about the adventure rather than simply the image itself.

Taking all of this into account, there may be an additional value to landscape photography (rather than landscape photographs) beyond the monetary and emotional ones mentioned above. Many YouTube landscape photographers (Henry Turner, Kim Grant and Adam Karnacz, to name but three) speak in their videos about the mental health-benefits associated with the genre. The process of planning, slowing down, getting out there and focusing on photography can be a balm to the soul. The Italian photographer Attilio Ruffo reasons that “the therapeutic benefits of being immersed in natural settings capturing these scenes can lead to personal healing... …the true reward isn’t always the photograph itself but the experience of being present in the moment.”

In contrast, using AI to generate landscape images generates neither monetary nor emotional value. There is no discernible provenance for AI images, no clear author who might impute value by virtue of their name, no scarcity associated with a flood of computer-generated images and certainly no emotional connection to them beyond the brief dopamine-hit associated with unlocking the right prompt to generate the image you had in mind.

Not only this, what we don’t cherish we won’t protect. If the images are cheap - whether monetarily or in terms of the effort required to obtain them - then we won’t value the resource that gives rise to them. There was no greater proponent of the American wilderness than Ansel Adams. When it wasn’t a camera in his hand, more often than not it was a pen as he tirelessly lobbied Congress to persuade them to create national parks. He cared desperately about nature and recognised that it was a resource that needed protecting. If we’re going to be satisfied with cheaply obtained images, we won’t care about their original inspiration.

Other Genres

What about other branches of photography? Might they be threatened by the AI-revolution? I can’t see AI replacing portrait photographers any time soon, or event/wedding photographers. People don’t generally want a picture-perfect set of photos with uniform smiles featuring unnaturally white teeth, they want a photo that evokes the memory of the day, with Uncle Phil’s rakishly lopsided tie, little Billy’s impishly-untucked shirt and Grandma being propped up by aunt Su after having one-too-many pre-reception G&Ts. The value of the image lies in the imperfections of the moment that are an inevitable by-product of human interactions.

Similarly, people don’t want an image of what a woodpecker might look like, they want a skillfully captured image in the field. The sports-press don’t want an image of what Harry Kane scoring that goal would have looked like, they want a documentation of the instant.

![Adobe Firefly AI Sports Image - Prompt: [harry kane scoring a goal for FCB at the allianz arena in munich in the rain]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/d14608_7e27a41b260a44b49dccbf6c3b0acfe3~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_980,h_762,al_c,q_90,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/d14608_7e27a41b260a44b49dccbf6c3b0acfe3~mv2.png)

The possible exception is the realm of commercial photography, where the priority is on creating desirability rather than authenticity.

Conclusion

In a recent discussion with one of the AUB lecturers, she mentioned that her undergraduates who - much like my own children - grew up in a thoroughly digital age, have a thirst for the analogue, whether film-based photography or vinyl-based music. People genuinely want to be hands on again rather than to be hiding behind a screen. The process of landscape photography, the planning, the skill acquisition, the waiting for the right conditions is another draught that will quench that thirst. Even if AI image-generation overcomes its emotional limitations (and that’s a big ‘if’), the simple generation of images via prompt can never equate to nights spent on a mountain waiting for the clouds to clear and the moon to set, can never replace the colours of a winter sunset over a snow-covered landscape. THIS is the true value of landscape photography.

Landscape photography won’t be a victim of AI-generated images, it will be an antidote to them. The long, considered process involved in obtaining images in the field is everything that the computer-based approach isn’t. Our experiences and our stories, the emotion that we can convey through the resulting images will be difficult to emulate and landscape photography can never be reduced to the image itself. It will always be about the story.

Comments